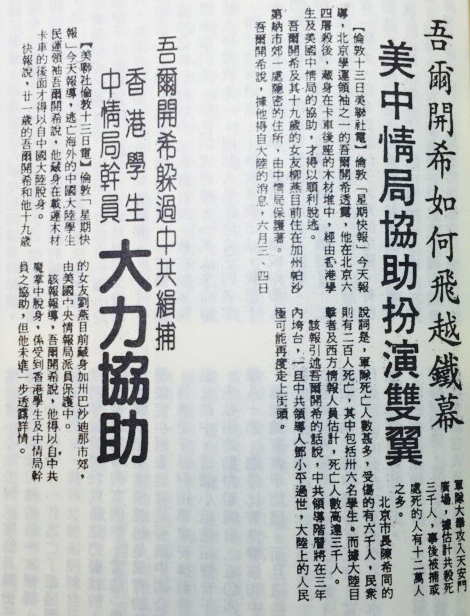

「黃鳥行動」首次曝光

中國的大逃亡

兩年前,在北京開始屠殺嚮往民主的示威群眾時,一條值得注目的地下管道曾經在中國秘密警察的監視下,成功地把至少130個中國異議學生和知識分子的頭目走私出境。

這種賣命走私的零零碎碎,被非正式地稱為黃鳥行動。為了避免危及將來的任務和參與的份子,這個行動從未公開。但是據救援人員所說,在一次逃亡行動嚴重失誤後,中國的公安當局--秘密警察,已經知道了行動的詳細內容,也因此,這個組織的一些成員首度在BBC的電視節目「全景」中透露了行動的細節,包括他們如何利用和欺騙共產黨的安全人員。

這個行動組織包含了40個人以上。它開始活動是在北京當局大為憤怒,也就是在李鵬的保守政權開始搜捕和監禁在中國首都的心臟地區參與和支持嚮往民主的示威活動的異議份子。

黃鳥行動經常用特別成立的貿易公司作掩護來派遣小組進入中國,它提供造假的文件和為被搜捕的男女偽裝,在有五次的逃亡紀錄中還從香港派出的包括了化妝師的逃亡小組,以幫助這些難民偽裝。

逃亡組織有管道弄到各種船隻和一般間諜使用的裝備,包括干擾設備電話,夜視槍枝和紅外線訊號器。此外黃鳥行動包括

■在公海中與中國海岸巡邏隊火力衝突

■亞洲黑社會幫助--三合會

■不少中共軍方及安全人員的秘密協助

在獲救人員當中有些是中國極力追捕的學生,包括吾爾開希和李錄;兩個政府的高級顧問和改革者--陳一諮和嚴家其,和被大力通緝的知識份子--蘇曉康。

黃鳥行動的贊助人是來自香港嚮往民主的同情者。在1989年5月,這些人已經成立了「支持中國民主運動聯盟」,並且在人民解放軍鎮壓北京之春的兩天之內--6月3日到6月4日,這些同情者決定要幫助那些在中國流亡的人。他們起草一份有40個異議份子的名單,他們認為這40個人可以構成被放逐海外民主運動的核心。某個人和這個團體結合共同創立逃亡的組織。

中國當局曾指控--前香港演員兼企業家約翰‧三(John Sham,岑建勳)參預這個行動。除了承認知道黃鳥行動的一些細節外,三(岑)拒絕評論中國的指控。在BBC的訪談中,他說:「這個行動有兩個迫切的難題」,「如何安置散佈在中國異議份子和如何救出他們。」

把異議份子搞出來顯得較為簡單,因為在中國和香港之間有相當數目的走私集團在活動,他們經常利用中國南海岸的眾多水道和島嶼,以舢板和其它船隻走私,從冷氣機、電視機到Mercedes(賓士)汽車的任何東西,而且還偷運出要到香港找工作的非法移民。很多漁民經營這種行業,但是有一些走私集團是由亞洲的犯罪組織--三合會所組成。救援者認定只有三合會有組織而且能保證救援行動的成功。

三(岑)說:「他們找上專家,找上這些走私犯。」三合會是個古老的犯罪幫派,有自己的入門儀式和各種手勢。它有全球性的網路,年所得估計有數億美元。香港三個主要的三合會頭目是14K〔全名:洪發山忠義堂,珠江水白雲香,廣州西關寶華路十四號〕、孫葉安和 Wo Shing Wo〔和勝和,簡稱勝和,是香港一個地道的三合會組織〕 他們控制整個區域內的賭博,犯罪和娛樂事業。香港警方估計在1990年一年中,走私到大陸的總值有兩億美元。

在北京屠殺一個禮拜內,香港一位最具影響力的大亨和救援行動的組織在九龍富豪酒店碰頭,同意立即救援。三(岑)說「他們在意識型態上同意民主運動」。三合會同意不拿利潤,但要求支付在兩岸邊界活動的費用。一般營救任務為五千美元一次,但特別出名的領導人則高達七萬美元。雖然三合會作了很重要的接頭,但是大部份參與救援行動的走私販並不是三合會的人。雖然香港廣泛支持民主運動,但是救援資金卻是私下募集,以免引起英國當局注意。在1997年香港殖民地歸還中國之前,英國政府堅持不願冒犯中國。但是在幾天之內,黃鳥行動已從英國商社中募到兩百萬美元。

在救援開始之前,這些異議份子還得先被找到。有至少一千人在天安門和其附近被殺,而很多異議份子在戰慄中逃離首都。軍隊和秘密警察拿著通緝名單徘徊在街道當中,北京車站成了危險地區。著名的學生領袖吾爾開希回憶說:「朝哪個方向望,都是一片綠海--警察跟軍隊的制服。」「他們檢查每個東西--並且沒有人微笑。每個人都帶著一張冰冷的臉。」具有自由思想的陳一諮,曾是現被打入冷宮的前總理趙紫陽的幕僚,回憶起在火車車廂的情景。「每個人都被痛苦所震驚,充滿了不信。人們散落各地,他們爭吵、詛咒,那是大混沌」。

在中國搞地下活動相當危險。每個居住區或是胡同都有受警察控制的委員會;在從前的鎮壓中,曾經證明他們是高效率的告密者。然而這一次雖然有一些學生被交給了警察,但是很多人卻受到同情者的保護。

吾爾開希回憶起在火車上被認出來的那一刻:有個人看著他的臉說:「真榮幸在此地看到我們的領導人,別擔心,車上的人都會幫忙,但是臉向外看,向外看,警察就不會看到你的臉。」

當異議份子往南流竄時,他們不只遇見表示支持的單獨個人,也遇見同情者組成的特殊網路。

蘇曉康因為《河殤》而名列通緝名單,《河殤》因為攻訐中國的落後而激怒中共高層官員。蘇在被某同情者的團體所接引後,隨之四處遷移。「某人來告訴我有個聯絡人將帶我走」。這個人就以他自己的名字登記房間,讓蘇居留過夜。「每次我要出城,我都不能去火車站,我都搭長程公車,經常有一個或兩個人陪我。他們來保護我,但是我們裝作彼此不認識。」有些保鏕付出慘重代價,某個幫助陳的保鏕判了12年牢,另一個則被折磨得神智不清。

在南方有一陣子,很多異議份子非常的危險。有些人聽說有個逃亡組織但是不知如何連絡。為了想看看自己在邊境告示牌上的名字,陳一諮溜近了邊界,他就這樣跑了出來。天安門廣場廣播中心的主編白蒙(Bai Meng 譯音,),在一次警察的追捕中跳窗逃出,卻不久就被一幫人捉住,他們聲稱認出白的真實份而要求金錢。當香港的團體接獲異議份子躲藏的地點,就非常小心地去辨認這些異議份子的真假。蘇曉康回憶起這個組織和他的第一次接觸,就是拿一張他兒子的照片給他看。「我逃亡了超過兩個月,當我看到我兒子的照片,我再也無法控制自己,不禁流下淚來,他們早就發現我就是他們要找的人。」

在吾爾開希的案例中,當他一張拍立得照片送到這個團體以證明這個連絡是真實的後,他們立刻派遣一個鑒定小組去證實是否為中國公安局陷阱。

異議份子得到指導來安排到香港的最後逃亡。在電話交談中,這個小組使用聲音干擾設備。

走私用的動力船裝有250匹馬力的引擎,航速可達80節,跑得比香港警察和中國海岸部隊都快。

駕駛艙有裝甲防護,而且這些小組還有夜視設備和紅外線訊號器。

吾爾開希最早成功逃亡出來。但是這個行動差一點搞砸。他在海岸邊等了三夜,當和走私船聯絡上後,他游了五百公尺,穿過海底的水泥暗樁。他上船時已經有嚴重擦傷和流血。

當逃亡次數增加時,走私者越來越依賴中國的警察和海岸部隊。有些人早就是貪污腐敗並和走私犯結盟,但還有其它人是因為同情學生。他們的協助反應出中國的現狀,也確保地下通道的成功。在某一省,有個高階警官還真的曾和一個學生共坐一部車旅行,以護送這個學生通過一個路檢。一個最近逃到西方的高級秘密警察告訴BBC,他和其它人在逮捕開始之前,就暗示學生逃走。

一個曾進入中國指揮行動的人說,他們有一些線民在政府部門、當地公安局、邊界部隊、海岸部隊,甚至在雷達操作員中。

要避開檢查也不是萬無一失。北京派了一千位情報軍警來遏止這些逃亡。蘇曉康曾經躲在一個安全的屋子,然後痛苦地花了兩天待在海上快艇的艙房。「我病了,全身發汗。我嚇壞了。」一艘海岸巡邏艇嘗試要攔截走私船,「朝著天空開機槍和來福槍示警」;救援人員說:「當他們對快艇開火,為了要逃,我們也還擊。」在一場逃亡槍戰中,一個救援人員肩膀受傷,至少有一個救援人員中槍。

北京有時採取報復,例如,當陳一諮躲在一艘小貨輪水箱下的秘密空間,安全地經海南島逃到香港後,中國的領導李鵬下令對島上居民採取報復,把四千人拘禁起來。「李鵬被我逃出的消息震怒。」陳一諮說:「我聽到這件事覺得很難過。」

當異議份子抵達香港後,很快他們就被四處驅趕。英國當局同意黃鳥行動的進行,但是要求這些被救出的逃亡者必須在不引人注意的情況下迅速進入第三國。這個組織向美國試探,以作為避難所,但美國堅持首先要作費時的安全檢查,這些救援者轉向法國,法國立刻答應收留這些人。

大部份的行動都是成功,但有一次失敗,結果把兩個重要的異議份子王軍濤和陳子明給送進牢裡。這兩個人在嚮往民主運動之前,就已經發出反對的聲音,中國政權把這兩人視為騷動的主腦。

救援者曾派了一個生意人Luo Haixing〔羅海星〕去和中間人接頭,討論藏身地和暗語。但是在10月13日,兩個黃鳥行動的工作人員在準備要把陳子明運到東皖城時被捕。這個生意人在回港途中被捕。黃鳥行動就這樣被出賣給情治單位,陳子明和王軍濤因密謀推翻政府給判了13年。這個生意人 Luo Haixing 判了五年。

但是各色各樣的聯絡人和走私路線還是讓逃亡行動繼續下去。就如一位黃鳥行動的指揮者帶著微笑所說:「這個網路破了,我們只是掉了一塊皮,但是我們還能再動。」

譯按:本譯自《華盛頓郵報》1991年6月2日,原標題為Escape from China。◆

THE GREAT ESCAPE FROM CHINA By Gavin Hewitt June 2, 1991

AFTER THE MASSACRE of pro-democracy protesters in Beijing two years ago, a remarkable underground railroad safely smuggled more than 130 of China's leading dissident students and intellectuals to the West under the noses of the Chinese secret police.

Details of the effort -- unofficially called Operation Yellow Bird -- have never been disclosed for fear of compromising future missions or those involved. But the rescuers say that Chinese State Security -- the secret police -- has extensive knowledge of their operations after one escape went badly wrong. And so for the first time, in an interview with BBC television's Panorama television program, some of the organizers have revealed details of an operation that took on and largely outwitted the security services of a communist police state.

The operation involved more than 40 people. It sprang to life shortly after the Beijing crackdown, when the conservative regime of Li Peng hunted down and imprisoned political dissidents who had participated in or supported the extraordinary month of pro-democracy demonstrations in the heart of China's capital.

Yellow Bird regularly sent teams into China using the cover of specially formed trading companies. It provided false documents and disguises for the hunted men and women, and on five occasions, escape teams sent in from Hong Kong included makeup artists who helped disguise the fugitives. The escape network had access to a variety of boats and equipment normally associated with covert intelligence operations: scrambler phones, night-vision gunsights, infra-red signalers. In addition, Yellow Bird also included: Armed clashes with Chinese coastguards on the high seas. The help of Asia's mafia, the Triads. Covert support of many Chinese military and security officials.

Among those rescued were six of China's most wanted students, including Wuer Kaixi and Li Lu; two of the most senior government advisers and reformers, Chen Yizi and Yan Jiaqi; and one of the most wanted intellectuals, Su Xiaokang.

The operation had its roots among pro-democracy sympathizers in Hong Kong. In May 1989, these persons had formed the "Alliance in Support of Democratic Movements in China," and within two days of the People's Liberation Army crushing of the Beijing Spring on June 3-4, the sympathizers decided to assist those on the run inside China. They drew up an initial list of 40 dissidents they believed could form the nucleus of a Chinese democracy movement in exile. An individual associated with the group began building an escape organization.

Chinese authorities have accused John Sham, an entrepreneur and former Hong Kong actor, of being behind the operation. Sham declined to comment on the accusations beyond conceding he knows some of the details about Yellow Bird. "The operation had two immediate difficulties," he said in a BBC interview. "How to locate the dissidents who were dispersed throughout China and how to extract them."

Getting the dissidents out appeared the easier problem to solve, for a number of smuggling networks operate between China and Hong Kong, regularly smuggling anything from air conditioners to television sets to Mercedes cars into the mainland in sampans and other boats that ply the crowded inlets and islands off China's southern coast -- and smuggling out illegal immigrants seeking work in capitalist Hong Kong. Fishermen run many of these operations, but some are also organized by Asia's societies of organized crime, the Triads. The rescuers decided that only the Triads had the networks and contacts to ensure success of their effort.

"They turned to the professionals, to the smugglers," said Sham.

The Triads, ancient criminal societies with their own initiation rites and hand signals, are worldwide networks with annual income estimated in the billions of dollars. Hong Kong's three main Triads are K 14, Sun Ye On and Wo Shing Wo. They control the territory's lucrative gambling, vice and entertainment industries. Hong Kong police estimate that smuggling into China totaled $2 billion in 1990 alone.

Within a week of the Beijing massacre, one of Hong Kong's most powerful dons met with the organizer of the rescue operation at the Regal Meridien Hotel in Kowloon and readily agreed to help. "They were ideologically sympathetic to the democratic movement," said Sham. "It was certainly not because of the money." The Triads agreed to make no profits but requested that their operatives on both sides of the border be paid. An average rescue cost $5,000 although some prominent leaders cost as much as $70,000. Although the Triads made important connections, most of the smugglers involved in the rescue operations were not Triad members.

Despite widespread Hong Kong support for the democracy movement, rescue money was raised quietly for fear of arousing British authorities, who are intent on not offending Beijing before the colony is returned to China in 1997. But in a few days, Yellow Bird raised $2 million from the colony's business community. Before the rescue could begin, however, the dissidents had to be found. At least a thousand people had been killed in and around Tiananmen Square, and many dissidents fled the capital in terror. Troops and security police roamed the streets with wanted lists, and the Beijing railway station was a dangerous place. "Wherever you looked was a sea of green, uniforms of police and army," recalled Wuer Kaixi, a well-known student leader. "They checked everything -- and nobody smiled. Everybody had a very cold face."

Chen Yizi, whose liberal think tank had advised the ousted premier Zhao Ziyang, recalled the scene in one railway car. "All were panic-stricken, in disbelief. People were shattered; they argued and cursed. It was chaos."

Going underground in China is hazardous. Every residential block or hutong has its arm-banded committee under the control of the police: In previous repressions they had proved energetic informers. This time, however, although some students were turned in to police, many were protected by sympathizers.

Wuer Kaixi recalled the moment he was recognized on the train. A man looked him in the face and said, "It is a great honor to see our leaders here. And don't worry, all of the people in this wagon will help you. But face out! Face out so the guards don't see your face."

As dissidents drifted south, they encountered not only individual gestures of support but ad hoc networks of sympathizers.

Su Xiaokang was on the wanted list for his film "River Elegy," which enraged some senior Communist party officials for attacking China's backwardness. Adopted by a group of sympathizers, he was moved from place to place. "Someone would come and tell me that a contact was arriving to take me on." This individual would book a room in his own name and Su Xiaokang would stay there. "Whenever I had to leave town, I couldn't go to the station. I used a long-distance bus. I was always accompanied by one or two people. They were guiding me but we pretended not to know each other." Some of the guides were to pay a heavy price. One man who assisted Chen Yizi got 12 years in prison; another was tortured and is now mentally deranged.

Once in the south, many dissidents became vulnerable. Some heard of an escape organization but did not know how to contact it. Chen Yizi tried to slip across the border only to see his name on a list in the border post. He fled. Bai Meng, who was editor-in-chief of the broadcasting unit in Tiananmen Square, once jumped out of a window to avoid a police raid and later was seized by a gang who demanded money, claiming to know his real identity.

The Hong Kong group began receiving information about where dissidents were hiding. Great care was taken to confirm that the dissidents were genuine. Su Xiaokang recalled that the organization's first contact was to show him a photo of his son. "I had been on the run for more than two months. When I saw my son's picture, I could not control myself any longer, and I burst into tears. They had discovered I was the right person."

In the case of Wuer Kaixi, a Polaroid photo of him was shown to the group to prove the contact was genuine. They immediately dispatched a verification team to ensure it was not a Chinese Public Security Bureau trap.

Dissidents were given guides to arrange the final escape to Hong Kong. In telephone conversations, the teams used voice scramblers.

The smugglers' power boats, with four 250-hp engines and speeds of 80 knots, could outrun both the Hong Kong police and the Chinese coast guards. The cockpits were armor-plated and the teams had night-sights and infra-red signaling devices.

One of the first successful escapes was that of Wuer Kaixi. But it nearly went wrong. He waited three nights on a beach before contact was made with a smugglers' boat and then had to swim 500 meters out to the boat through water dotted with submerged concrete posts. He reached the boat badly grazed and bleeding.

As the escape numbers grew, the smugglers relied more on their contacts in the Chinese police and coast guards. Some were corrupt officials already in league with the smugglers but others sympathized with the students. This assistance, which reveals much about the present situation in China, was crucial to the underground railroad's success. In one province, a senior police officer actually traveled in the same car as a student to get him through a roadblock. A senior secret police officer who recently fled to the West told the BBC that he and others tipped students off if an arrest was impending.

One man who went into China and commanded some of the operations said the organization had contacts in "government departments, local public security bureaus, border troops, the coast guards, even radar operators."

It wasn't always possible to evade detection. Beijing brought in a thousand military intelligence troops to try to prevent the escapes. Su Xiaokang, who had hidden in a safe house, spent two hours in a harrowing offshore speedboat chase. "I felt sick and I was sweating all over. I was gripped by terror." A coast guard patrol tried to intercept the smugglers' boat, firing "machine guns and rifles in the sky as a warning," said a rescue operative. "And then they fired on the speedboat. In order to escape we returned fire." After a running gun battle, the smugglers escaped, with one of the rescuers wounded in the shoulder. Shots were fired on at least one other rescue.

Beijing sometimes took reprisals. For example, when Chen Yizi was safely smuggled from Hainan Island to Hong Kong, hidden in a secret compartment beneath a water tank on a small cargo ship, Chinese leader Li Peng ordered reprisals against the islanders, taking more than 4,000 into custody. "Li Peng was overwhelmed with anger when he heard that I had escaped," Chen Yizi said. "I felt very bad about hearing this."

When dissidents reached Hong Kong, they were quickly hustled elsewhere. British authorities had agreed to allow Yellow Bird to continue so long as rescued dissidents left silently and quickly for a third country. The organization approached the United States as a possible haven, but when America insisted on time-consuming screening first, the rescuers turned to France, which immediately agreed to accept them. Most of the operations were successful but one failed, sending Wang Juntao and Chen Zeming, two of China's most important dissidents, to jail. The two, voices of opposition even before the pro-democracy movement, were considered by the regime to be among the masterminds of the unrest. By October 1989 they too had moved south and were in hiding.

The rescuers sent businessman Luo Haixing to meet with an intermediary. Hiding places, false names and code words were discussed. But on Oct. 13, two Yellow Bird operatives were arrested as they prepared to move Chen Zeming to Dongwan City. The businessman was seized on his way back to Hong Kong. Yellow Bird had been betrayed to the intelligence services. Chen Zeming and Wang Juntao got 13 years in prison for conspiring to subvert the government; businessman Lui Haixing got five years.

But the variety of contacts and smugglers' routes is so great that escapes continue. As a Yellow Bird commander put it, with the trace of a smile, "The network was broken. We shed a skin but we can still operate."

Gavin Hewitt is a correspondent for BBC Panorama. in London.

社論

國際視窗

美國與西藏

統獨問題

美國對華政策

兩岸關係

大陸事情

座談會

每月專訪

通訊

編輯室報告